One of Five Arts Centre's closest collaborators, Wong Tay Sy is pulling double duty as production designer for both ANGGOTA and A Notional History - the first two performances in our new space in GMBB, Kuala Lumpur.

Ahead of both performances, Tay Sy reflects on her interest in the performing arts, and shares her approach

to production design. Trained initially as an artist working with a sculptural and installation tendency, she

often works alongside her brother David Wong in Maroon Art & Design - the go-to set builders in the Klang

Valley for projects ranging from large-scale musicals to intimate experimental performances. In her own work,

she is particularly interested in collective creativity and interdisciplinary collaboration. Tay Sy was also

a member of the artist collectives SpaceKraft and Rumah Air Panas.

More info about ANGGOTA and tickets at www.cloudtix.co.

1. It's been over two decades since you became involved with production design for theatre and film. Could you share how you began working more within the performing arts?

I was trained in visual arts, but back then perhaps I couldn’t understand why creating a painting or making a sculpture did not satisfy me. Looking back on my 22-year journey in the arts, I realized I am really interested in working with people - people that are really interested in their work. I am interested in working with people who are passionate and believe in what they are doing, and see themselves as part of a larger eco-system. I am interested in working with people who care and are willing to share.

I have worked across visual arts, performing arts, and filmmaking. I must say I am lucky to have met quite a number of people from these different disciplines who possess the qualities I mentioned. Art can be created in any form - the makers are the ones who determine the final outcome. But I think what has caused me to work more in performing arts is because I have built very long-term collaborative relationships in this particular discipline compared to others. And I am still continuously meeting people with these qualities - in the field of performing arts, locally and internationally. It keeps me wanting to continue what I am doing, as well as pursuing the question of what I want to do within this art form.

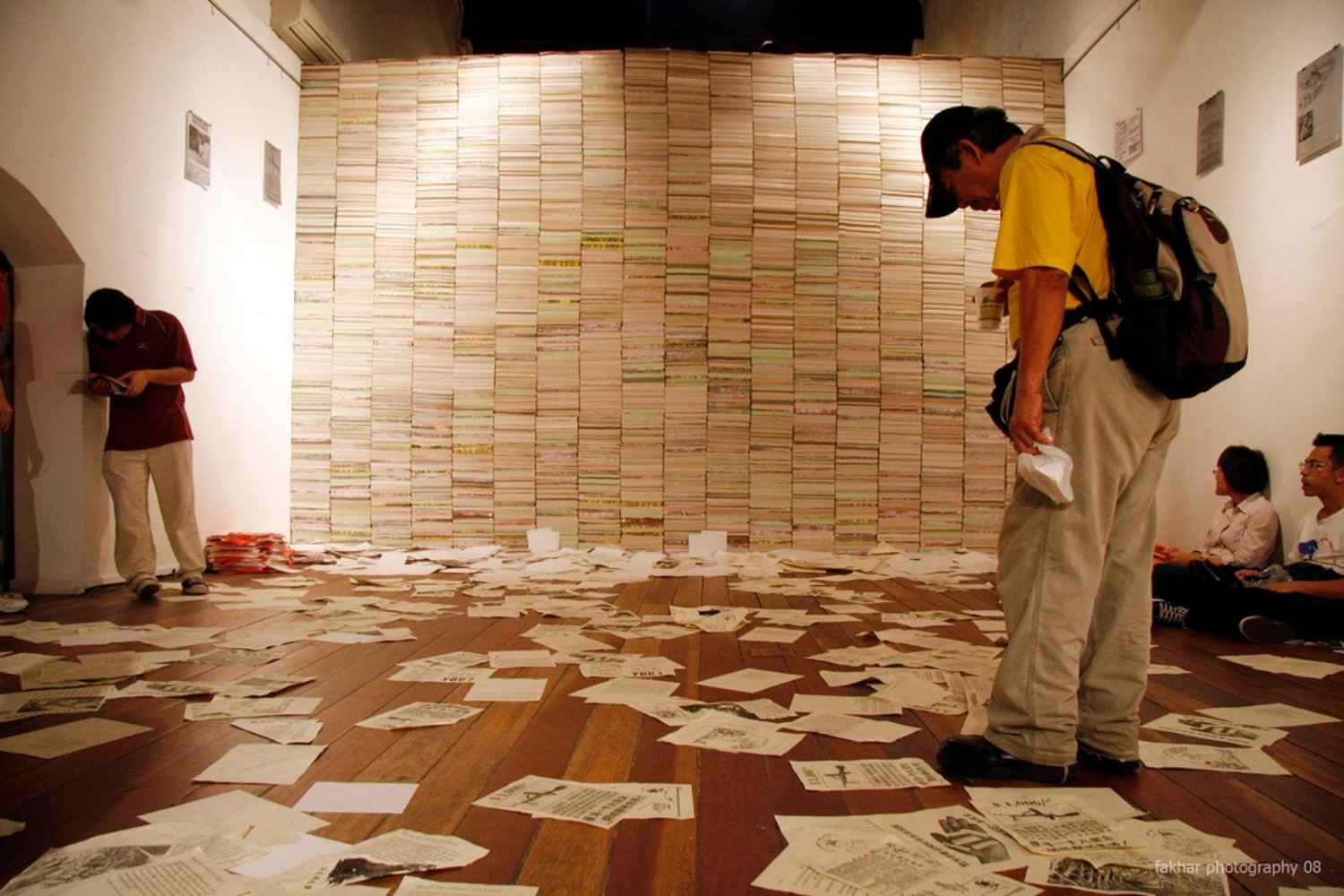

2. In your collaborative projects with Mark Teh such as Something I Wrote, Baling, Version

2020, and A Notional History, your production design always allow for a

transformability in the materials, objects, or structures onstage. The spatial elements and images created

often suggest an instability or restlessness - things are always changing and never really settle. These

transformations are often executed onstage by the performers themselves, and not by stage crew or mechanical

means. There also appears to be a concern to work with everyday or inexpensive materials.

What are some principles or questions you begin with when you approach a design for a performance?

Although I have been in the arts for more than two decades, my work as a production designer only became more regular in the past 10 years. To be frank, I have only done production design for not more than five directors across performing arts and film. I am very picky with production design work because I know I need a long, ongoing bouncing of ideas and interactions with the director before I can concretize my ideas. Any director who is unable to go through this process with me, I cannot see myself working with them.

My work with my brother David - on set building and props-making - causes me to pay attention to how things are constructed and made. What are the mechanisms, scaffoldings and facades that make a prop or form a set? Parallel to this, my long-term work with a bunch of history geeks also helps me to read things in a much more 'deconstructive' manner.

So when I am asked to production design for performing arts, I will bring in raw materials and everyday objects for the performers to play. Through these explorations, I will see images that form or suggest different layers of meaning, and I will propose them to the director. I am interested in exploring how everyday objects or raw materials, especially construction materials, can take on multiple meanings. I am also interested in appropriating objects and costumes from their original design and function to create different meanings. This constant shifting and unsettling reflects the state of the human condition in urban life especially.

Art is like a window that is framed by artists, and allows people to see the worldview of the artists. Art has the power and ability to rock people’s minds and reflect something they may have taken for granted. Art helps to open more possibilities and perspectives. My strategy to invite the audience to the world created by me and my collaborators is often to start with objects and images that are familiar to them. Hopefully they will see multiplicity when they enter that world, and appreciate an ambiguity that may not have been encountered previously.

3. You're currently the production designer for the first works to be staged in Five Arts' new space. On the surface, Lee Ren Xin and Tan Bee Hung's ANGGOTA and the documentary performance A Notional History appear to be very different works. ANGGOTA is a new dance creation and you're collaborating with Ren Xin for the first time, while you've had a very long relationship with the people in A Notional History. What are some discoveries during this process of working on two projects very closely next to each other, within the same space?

ANGGOTA is really a very new and interesting project for me. It is my first time working with Ren Xin, Bee Hung, Chloe Yap and Veeky Tan in a contemporary dance piece as production designer and producer. It just happens to be all women and all Chinese - which I jokingly said is "So not Five Arts Centre!". Ren Xin is a friend and someone I've always wanted to work with. Her approach to things and people around her is really different from me - she senses things through her body. Through our conversations together, about work or everyday life, I see my own ignorance or lack of awareness. It makes me more reflective, and reminds me to be more sensitive to my surroundings.

A Notional History is a work that has travelled to three countries. But this is the first time we are going to stage it in Kuala Lumpur to our local audience - it has been postponed several times because of the pandemic and MCOs. People like Mark, Syamsul Azhar, Faiq Syazwan Kuhiri, Fahmi Reza and Rahmah Pauzi are my regular, long-term collaborators, and over the years we've worked together to make everything from small arts festivals and exhibitions, to theatre performances and documentary films. Because of this multiplicity and flexibility within the group, I know that A Notional History is a work that can be staged in different spaces - from black box spaces, to classrooms, or a library, for example.

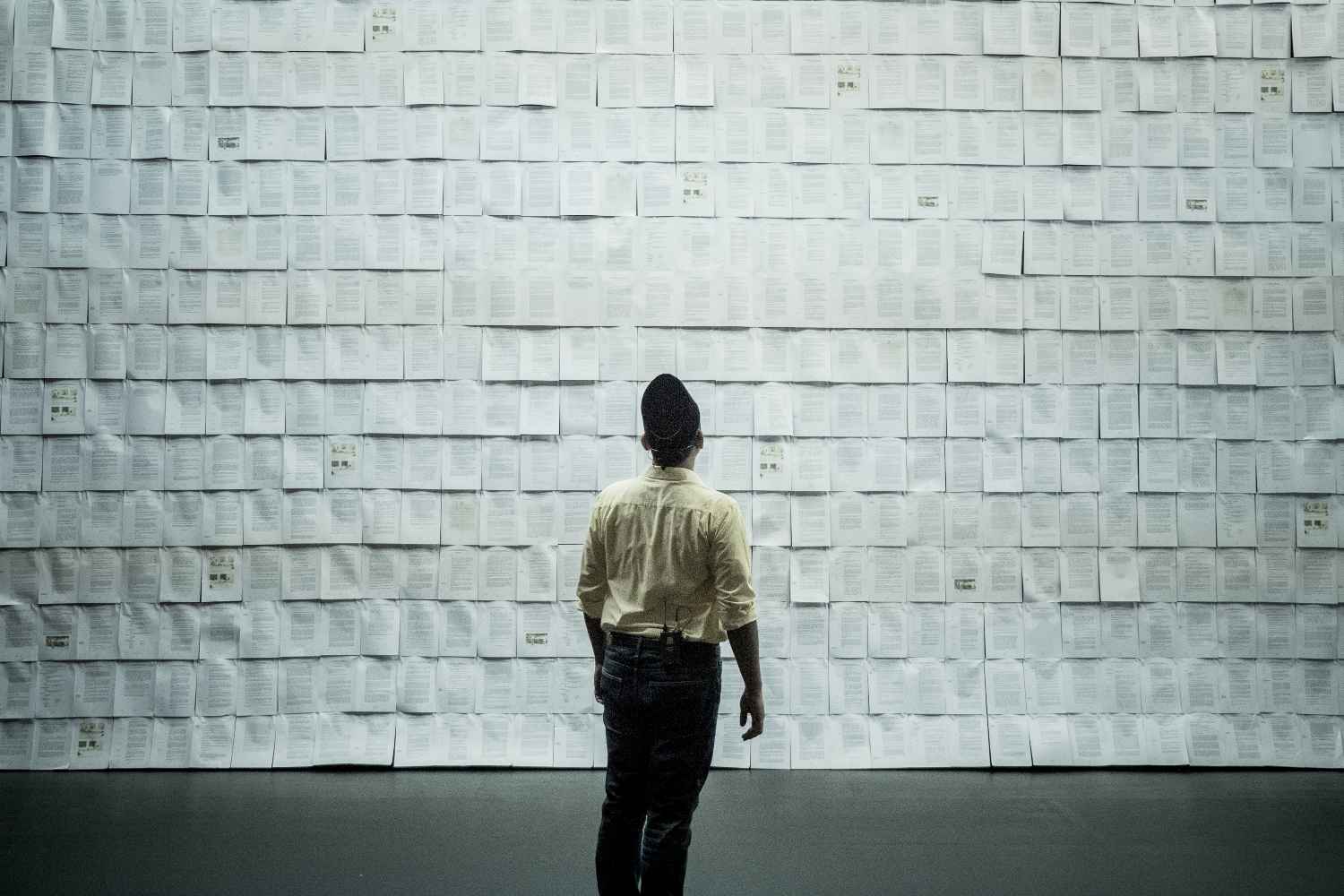

Although I am designing for two very different shows - contemporary dance and documentary theatre - there is

one common element that cuts across both. And that is the flexibility to adapt and appropriate materials

within the performance space. That is the strength of the black box - a controllable space which allows for

freedom to form and shape interesting, challenging views to the makers as well as the audience. For now, I

can reveal that the production design for ANGGOTA is more fluid and organic, whereas A Notional

History is more static but transformative. But both, in many ways, are equally unsettling - constantly

changing in different manners.

More info about ANGGOTA and tickets at www.cloudtix.co. Read Lee Ren Xin's answers to '3 Questions' on ANGGOTA here.